Imagine being told during childhood that your ovaries had to be removed or you’d develop cancer and die—only to learn in adulthood that was a lie, that many things you’d been told about your body were false and that the surgery you’d had wasn’t even necessary.

Last week I had the pleasure of interviewing Seven, a survivor turned thriver who lived this journey. The internationally recognized counselor and addiction expert is also the world’s first out intersex standup comedian and actor in Hollywood. Their story is one I feel everyone needs to hear and learn from. It has the potential to save and bring healing and understanding to many, many lives.

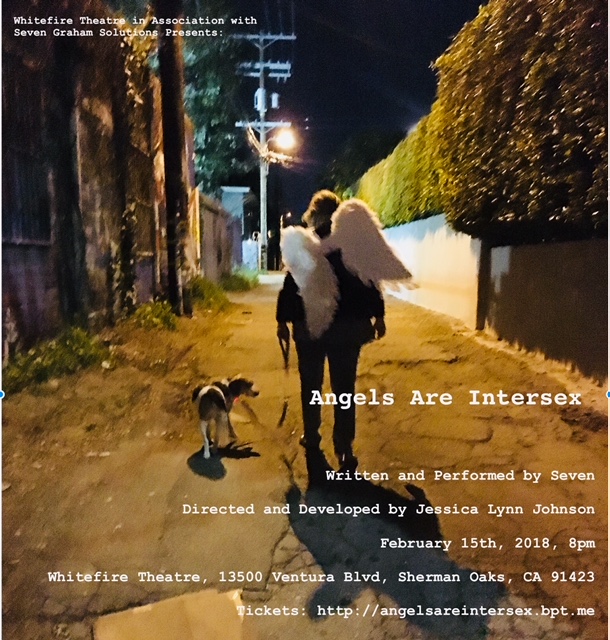

Stream the full Girl Boner Radio episode on iTunes, iHeartRadio, Spotify or down below! Read on for (very) partial transcripts, featuring a few highlights and powerful takeaways. If you’re in the LA area, please catch Seven’s original play, Angels Are Intersex, at SoloFest at the Whitefire Theater in Sherman Oaks on 2/15/18! Nab your tickets here.

AM: That must have been really terrifying, hearing the word cancer—as it would at any age. Being that young, did you grasp the magnitude of what that could have meant?

7: What I did grasp was I knew at eight that I wouldn’t be able to have children and I could see that this was a desperately upsetting situation for my mother especially—and also of course my whole family was upset I had to have surgery. I didn’t really have any clue what was happening, though, because I was a child.

I had to really bottle my feelings up and kind of push my feelings aside because I felt I needed to be brave for the grown-ups around me. And I was constantly being told by Sir John Professor Dewhurst [a respected gynecologist] that ‘you’re a very special little girl.’ So I felt like I had to perform being special and brave and let all his medical students examine me…which in retrospect was enormously damaging and created a schism between me and my body and created all sorts of problems going forward.

AM: Why are you being lied to? So the doctors could do this research?

7: Why I and many, many intersex people were lied to—and some still continued to be lied to—was because of a guy called John Money. He was a psychologist and had a case study where two baby boys, twins, had a circumcision and one of the circumcisions went wrong. It was decided that it was better for this little baby boy to be turned into a girl and raised as a girl rather than be a boy without a penis. John Money spent his professional life writing about this case study as a glorious success in nurture over nature. He said that the parents were told to raise the child as a girl and this happened successfully.

That trickled down to people like Sir John. He genuinely believed if he didn’t tell my parents that my sex wasn’t actually straightforwardly female, that my gender wasn’t straightforwardly female, that the socialization process would be more effective and that I would accept my gender identity of girl.

But the reality is that from a very early age, I knew that I didn’t fit neatly in the female box. I liked toys across the spectrum. I like playing with boys and doing boy things more than girl things actually. And I think it would have been a relief to me if I had been told the truth at that point because it would have made sense of my actual experience.

AM: So when you were 12 years old you learned more information, including that you did not have a womb, when many of your peers were probably going through puberty. Were you expecting not to menstruate because of the surgery?

7: I was kind of told little pieces of information along the way from eight years old when I had the operation. I then had to see Sir John for many years, every six months. And actually, that was medically unnecessary. There was nothing happening in my body that really needed to see doctors every six months. But he would parade me in front of his students basically to use me as a kind of case study.

When I saw a different gynecologist when I was about 14 they told me that I didn’t have a womb and so I wasn’t going to have periods. He did that in a completely matter of fact way: ‘Oh yes you don’t have a way I’m so you’re not going to have periods.’ He also said to me ‘and of course you’re not going to have much pubic hair or any pubic hair as well.’ These pieces of information delivered so much as matter of fact exploded on me in a kind of shame bomb.

AM: Do you remember talking to anyone about this or did the shame keep you from talking to friends or your parents?

7: I didn’t talk to anybody. I just felt too much shame. Another piece of this jigsaw puzzle—and this is common to intersex people—because there were no boundaries around my body and I had no sense of my body being my own, I started being sexually abused quite soon after the operation by a teenager… That started a pattern of being sexually abused and exploited by older people through my teens which created a sense of distrust of other humans and a retreat from humanity until the only kind of creatures that I really trusted were dogs and cats and other animals. I moved away from trusting humans and wanting to talk about personal things with humans because it didn’t feel safe… I’m considerably older than eight years old, and I’m still working on that trauma today.

This is one of the reasons why I am an activist around trying to educate people to stop the surgery on [intersex] children and infants. And to let people be intersex as a category, as a third space, because I think that nobody really understands the impact of that trauma. Most of it goes unseen or undiagnosed. Many intersex people self-harm, develop addictions, have unhealthy relationships, live in shame and fear and self-hatred. And we as a society don’t know about that because it’s not being talked about and it’s not being seen in the media in any way either.

AM: It’s incredible to me how little is known or discussed, especially considering how common being intersex it is.

7: The stats vary, but I’m certain you are right to say intersex is as common as red hair and green eyes. So everybody out there listening to this podcast will know an intersex person. But that intersex person may not be willing to disclose and is probably living in a lot of fear and shame.

AM: I’d love to talk more about the addictions you developed in response to the trauma and all of these realizations. What was the turning point when you went from realizing all of this to finding those kinds of coping mechanisms, or attempting to cope through substances?

7: I know that many things cause addictions in humans, but it’s a combination of things usually and often there is a genetic predisposition. There’s a lot of addiction in the [Scottish] side of the family. Both my maternal and my paternal great grandparents were alcoholics. So it was partly that. It was also partly the trauma, which started so young and I think sort of turned on the addiction gene. Then my mother left the family when I was 14 and I went out and found cannabis and speed.

And like many addicts I’ve worked with, I would say that drugs and alcohol were a solution for a long time. They were the solution to the pain that I was in. I had two suicide attempts when I was 14 years old. I really do believe I probably wouldn’t be here still if it hadn’t been for alcohol and drugs in terms of medicating the pain that I was in. They helped me experience positive things.

In terms of the subject of your podcast, I don’t think I’d probably have had sex if it weren’t for alcohol and drugs as well. Because alcohol and drugs gave me the kind of the courage and the kind of belief that I could be desirable. That helped me to have sex, not in healthy relationships certainly… I lost my virginity to a pedophile for example. It was pretty horrific. But I am very lucky in that when I did reach rock bottom with drugs and alcohol, when I was 32, I was a television director. I was privileged and I was able to pick up the phone to a rehab and go and do treatment.

AM: At what point did you realize that you had a problem you needed to address?

7: I had this view of an addict or an alcoholic as somebody who can’t work and who has to drink and use every day. And for many years my pattern of addiction was binge use. So I would be very, very healthy for most of the week—cycling to work, eating super healthily and going hitting the gym a lot. And then at the weekend or when I was in a situation where I was going to start having a drink all bets were off… I would say to myself, ‘I knew that I had a problem with cocaine before I knew that I had a problem with anything else.’ Because right from the word ‘go’ with cocaine, if I had one line then I wanted another and another and another. I could see quite clearly that I couldn’t control my cocaine use.

I had my first real consequences in 1997 where I lost a job because of my partying. That was the first thing that happened to me when I couldn’t deny that my use had affected my ability to perform at work. I got another job very quickly afterwards at MTV, which was not a good place at that point to get a job, as somebody who’s trying to stay away from cocaine.

I lost that moment of awareness I had in 1997, and it took me from ‘97 to 2001 before I finally realized that I was the out of control person I had always looked down on. The thing that happened in 2001 was my father died. I tried to control those feelings of grief and loss with all the things that I’d used for many years and none of them worked anymore. The grief was too big and nothing I could do would push it away and I relapsed the night of his funeral.

AM: What was the first proactive step you took to get out of that place and begin healing?

7: Somebody who I used to party with, a lovely guy called Mark, came to my house. I was at that stage where I couldn’t leave my house unless I was going to score and I was just drinking from first thing in the morning. He came to see me and looked completely different to the previous time I’d seen him. And it turned out he was six months sober at that point. And he carried the message to me that recovery is possible and I didn’t have to carry on living like that… Thank goodness, I was in the situation I could go to rehab.

AM: You’re helping so many people to feel less alone, and that you share so vulnerably is so courageous. Would you share a piece of advice that helped you during the darkest times that might help someone listening?

7: I think the most important thing that happened to me in my rehab journey was when my counsellor Richard said to me, ‘You have to tell people about this. You have to find the courage to start letting people know who you really are. Because if you carry on living the lies that you’re living, you’re not going to survive your addiction will take you down again.’ Which is really true when you have addiction. The secrets keep you sick.

The reality is that nobody has rejected me in the way that I rejected me. I have met nothing but a loving response from everybody that I’ve told about my body. I’ve got an incredible partner, Jessica, who really accepts me for me. I found true love and if you are who you are and you let your light shine, other people respond that. So that’s what I would say: Let your light shine. Don’t be cowed by the shame of this experience. Whatever your experiences, be yourself. Be truthful.

I think it is horrible that any person, let alone a multitude of people, are treated this way.

Good for you! Great that you share and talk. I need to learn also.

I have never heard the term “intersex”. I will be looking that one up, though I have an idea.

Thanks also to you, August.

Scott