After a difficult pregnancy, traumatic childbirth and near death experience in the hospital, Renée Schuls-Jacobson endured “next level insomnia.” Little did she know the dark places her attempts to feel better would gradually lead to. Her story is also one of healing, hope and vibrancy—in the Girl Boner department included. ;) Learn much more in this week’s Girl Boner Radio episode!

Stream it on Apple Podcasts/iTunes, Amazon Music, iHeart Radio or below. Or read on for a lightly edited transcript.

“Becoming Unf*ck-with-able: Renée Schuls-Jacobson’s Story”

a lightly edited Girl Boner Radio transcript

Renée:

People in the recovery community talk about windows and waves. We talk about how it’s not a linear healing, this thing. So it’s not like when you cut your hand and you just notice that, it scabs and eventually falls off. It’s not like that. You have some days that are better and then days that are worse. That was not my experience. I was just awful the whole way until this one day where I had this one good hour. It was heaven sent, because I really needed that hour to feel like, Okay. For whatever reason, that happened. And so I know that it can happen again.

August (narration):

That was Renée Schuls-Jacobson. I met Renée years ago. We were both writers in the blogging world. I knew she’d been a teacher, that she had a son. She seemed kind, smart and upbeat, like someone I would have liked to grab coffee with.

Then, seemingly out of the blue, in 2013, her routine blog posts stopped appearing. Some seven months later, she published a post, sharing why. She had been recovering from a dependency on a drug she had been prescribed. She’d been using it as directed. The problem was, those directions were quite wrong.

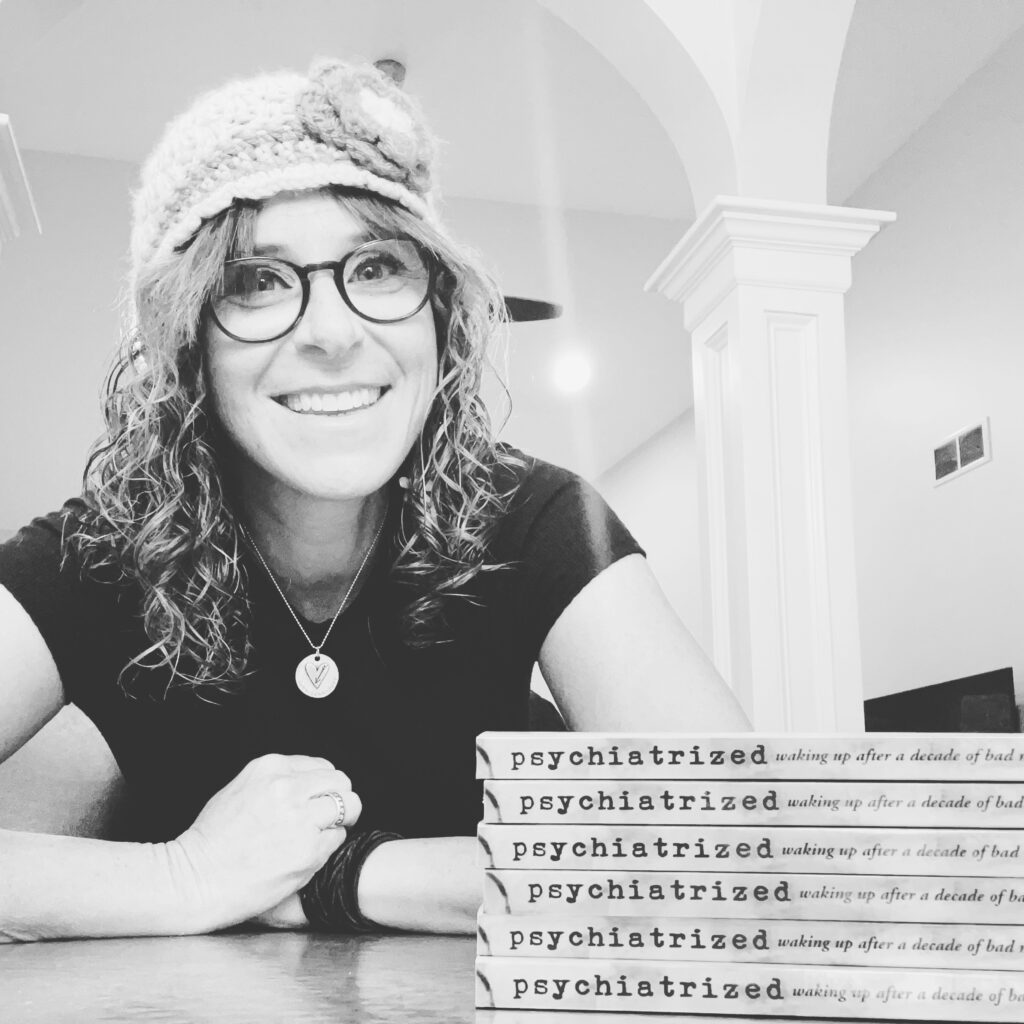

Renée is in a far healthier place now, and she recently published a powerful memoir called Psychiatrized: Waking up after a Decade of Bad Medicine. It’s a harrowing tale of her journey through dependency, injury and trauma, as well as a beautiful story of healing, hope and resiliency.

Before we dive in, I want to make it clear that I strongly believe in the helpful importance of psychiatric medications, when they are prescribed properly. That was not the case for Renée, and as she will caution you as well, it’s important not to make any changes to your medications without approval and guidance from a qualified professional.

Secondly, this episode contains material that may be sensitive for some, including details about a traumatic childbirth, sexual assault and suicidal ideation. As always, please take care of yourself first. If you are struggling with suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255.

[encouraging, acoustic music]

Today, Renée describes herself as an artist, author, advocate and fierce truth teller. As a kid, she was more of a “good Jewish girl,” in many ways. At the same time, she learned more than many kids do about sexuality.

Renée:

Even though I grew up in a pretty conservative family, Orthodox Jewish – conserva-dox, Jewish family, my mom was very open about sexuality. Very young, she taught me about the specifics of the, you know, way babies are born, the facts and things.

August (narration):

Her mom had quite a collection of literature, books of all kinds. And Renée was a voracious reader.

Renée:

I remember stumbling onto this book, The Happy Hooker, and some other very graphic books and asking her about them. And instead of like shaming me or shouting at me and saying “Those aren’t for you!” she sat down with me and told me all about like, the other side of sexual pleasure – that like, men and women do this to each other. And, and sometimes men and men do this, and sometimes women in women, and she was very open. She told me maybe a little bit too much about herself with her, my father, and no one necessarily wants to hear that. But point being, she was quite open about it.

August (narration):

Even if her mother hadn’t told her all of that, Renée would have had some idea.

Renée:

God, I hate to even say this because it might embarrass her, but we grew up in a pretty small house. And my parents are very deeply in love with each other. And you could, shall we just say, hear that at various times of the day or night. And um, I just kind of grew up with that, like, knowing that was normal. And that was like their normal expression. And my brother and I would kind of go downstairs to play when that was happening, or we would, you know, go do something else.

The caveat is that, even though she said that this was acceptable with other people – you know, men and men and women and men – it was, or women and women or men and women – it was always, always very clear that for me, it should always be in the confines of a sexually monogamous, preferably marriage relationship.

August (narration):

The positive messaging Renée received helped her grow up without shame around her sexuality, at least early on.

Renée:

When I was in middle school…I had a bunch of friends and we just hung out, we would go in the basement, we would play Duck Duck Smooch, and then we’d play Seven Minutes in the Closet. There was a lot of physical touch. And there was no stigma or shame around any of this. We could kiss each other and touch each other. It was just very innocent. It felt very innocent to me.

August (narration):

I loved hearing how normalized and joyful that was for her, which also made something else she experienced during high school all the more heart wrenching.

Renée:

So I was a pretty serious gymnast. I went several times a week to this training center, for years actually… It was a very confusing time. I went on the day that the gym was being closed. So I actually showed up—I think it was a Tuesday afternoon—and I had my leotard and everything in and the door was locked. And I had to sort of bang on the door. There were these people who actually were carrying out the lockers – like my locker, which had my leotard and my dance shoes and some other things in there. It was being carried out.

August (narration):

Renée didn’t know what was going on, but it was clear that the gym was being closed for good.

Renée:

Shortly thereafter, I found out about what was happening, that the coach had been accused of molesting several of his gymnasts and I remember thinking, well, first of all, what is that? Like what does that mean, the word ‘molest’ or ‘molestation? I’ve always been a bookish girl, so I looked it up, and I read it and went, Whoa. I trusted this person. This was an adult that I trusted. He had never acted out with me.

But then it created this strange place in my head where it was like, maybe I wasn’t good enough for him to have wanted to, like I wasn’t good enough. The girls that he selected were his favorites, or the better gymnasts or whatever. So it was this very strange seed that was planted that somehow the girls who were—I mean, now I see it as the girls who were victimized, right? Like the girls who were selected or groomed to be in this situation. They were the best. And I was kind of like, ah, man, I’m not that good. So it was a weird thing. I was relieved that this didn’t happen to me, but also felt simultaneously rejected. It’s a very strange dynamic.

August:

Completely. And it really mirrors the ways that, girls especially, in our culture – we learn that our sexuality is something that we give to people, that people do to us. We’re so objectified. And that you absorbed that message in such a violent way…

Renée:

Totally. And it carried into my high school life, academically in a weird way, because I was not necessarily the best student when it came to math. And there were a couple of male teachers that I would have to stay over after to get some extra help or assistance. And they were creepy, you know? And so I felt like I needed this help to be able to get better, like the way I would have with a coach, right? I was reliant on these people for their attention. They were a little creepy, but I had to sort of accept this idea.

And like I said, it got a little convoluted in my mind, but somehow it felt like if someone was touching me, then I was cared for in a certain way. It was very strange, but this did happen. Like there was a particular math teacher who would drop his pencil and he would kind of playfully look up my skirt or brush against my leg. And that’s not okay. But I felt chosen because of that… I don’t think I would have ever even had that paradigm if this earlier stuff hadn’t happened. I think I would have been furious, actually. But because this earlier thing happened, I definitely felt kind of like, oh, now I’m being now I’m being picked.

[minor jazz guitar]

August (narration):

While I was reading Renée’s book, I was struck by these two almost personas, almost a dichotomy that I think so many of us who were reared as girls experience. There’s the “good girl” she tries to be, which is all wrapped up in these super confusing messages, and there’s the person she would be without all of that. I don’t think that person ever goes away; they just get quieter or pushed down too often.

At one point in the book she wrote, “As I grow older, I not only feel pressured to be ‘good,’ but I also feel increased pressure to be socially successful, academically excellent, smart, fit and pretty, too.”

Once Renée met her former husband, Derek, in 1990, she found herself striving again to be that “good girl,” to be a “good wife.” She and Derek had things in common, and there were major differences between them. Renée wrote that she had always had a robust libido, for example. Sex is something she’s into. And Derek? He seemed to have very different values and needs.

When they met, Renée was dating someone who played drums in a band. Derek was in that band.

Renée:

We were just friends and he was the guitar player and he was very good, and we developed this friendship…and then it deepened as a friendship. But once things with the drummer fell apart and disintegrated, and I moved into my own place, and kind of was expanding into this apartment, in this new single life again. He kind of stepped back in and said, “Hey, would you like to go out sometime?” And I had never thought about him romantically before. He just felt comfortable.

August (narration):

Like Renée, Derek is Jewish. And he, too, was a student at the time, in medical school.

Renée:

And he was also creative, you know, a musician. And so we had a good thing. He was also just very kind. We got each other. We knew some people in common, all that stuff. So it felt very comfortable. But looking back at it now, August, I can see how it was a friendship, that we hit this precipice where it was, like we went out on a date, and it was a good date, and then came back to my place. And we kissed and I didn’t like the kiss. And, I mean, this is very painful. I didn’t even put this in the book.

August:

You didn’t feel chemistry.

Renée:

But I liked him so much. And because I didn’t have that experience behind me – I was young – I just thought, well, maybe we can build on this, right? Maybe we can build on this. And, you know, we tried.

For me, it was very confusing. I felt a lot of love. And my love language is definitely physical touch. So I tried. I would try to reach out. I would try to be affectionate.

August (narration):

But it was not received well or reciprocated. At first she thought, maybe it’s because he’s a doctor. He had gone from his residency into his internship and it was a very stressful time.

Renée:

And so he would say, “I am exhausted,” you know, give me those kinds of things. And at first I accepted them, but it was so early on in our marriage, I was like, this seems strange.

I’ve been in other relationships where we would at least make out or explore each other for hours and this just didn’t have it.

August (narration):

That was the case from early on, even before they were married. When Renée’s early attempts at building that spark of passion and affection didn’t pan out, she sought answers elsewhere. She didn’t know about therapy then. Given her religious background, she went to see a rabbi.

Renée:

Just prior to our wedding, I explained that we’re having some what I felt were some pretty significant intimacy issues, and the rabbi said, “Eh, you’re a teacher, yeah?” I said, “Yeah, I’m a teacher.” And he said, “You’re you’re pretty girl. Just be patient with him. You’ll be able to pull him out of his shell.”

And I remember feeling like, not only was I indicted as a bad teacher now, like if I couldn’t pull him out of his shell, not only am I not a good teacher now. And on top of that, I’m not sexy enough, or I’m not doing something right. Like if I can’t do it, I’m not doing something right. It made a huge impact on me. Huge.

August (narration):

Just before her wedding, during the summer of 1995, Renée confided in her mother, too – the woman who was so open about sexuality while Renée was growing up.

Renée:

I did say to her, “I’m concerned because we just don’t seem to have the kind of intimate connection that I would like.”

August (narration):

For whatever reason, that didn’t end up helping either.

Renée:

Maybe I wasn’t expressing myself as clearly as I needed to, or maybe she just didn’t want to hear it because she really loved him and wanted us to be married…. But whatever it was, she asked me a set of questions that really didn’t answer the question: “Do you think he’s fun?” “Well yeah, of course I think he’s fun.” “Does he make you laugh?” “Absolutely, he makes me laugh.” And then she said, “So, what are you worried about? The rest will come… The rest will come in time.”

And it seemed to be the message that everyone told me is that, you know, this will develop. This will develop naturally. And it just didn’t.

[soft, jazzy guitar]

August (narration):

A few years into their marriage, Renée learned that she was pregnant. Both she and Derek had wanted to become parents, and she called her son’s birth the “wonderful outcome of [their] union.” His birth was also traumatic, and her pregnancy leading up to it, very difficult.

Renée:

I had this extreme nausea the entire way. I actually lost weight during the pregnancy, which is always alarming. You know, that’s not what’s supposed to be happening. You’re supposed to be gaining weight. I was quite sick for a while. I was actually teaching early on and I had to take a leave of absence from school.

August (narration):

She was on bed rest and spending a lot of time alone.

Renée:

My husband went to work. And it wasn’t like I had visitors. People were working, you know? So I was very lonely.

Then one day, I actually got up and went to the bathroom, and then it just sounded like I was still going to the bathroom. But I wasn’t anymore. And I looked down and I was just gushing blood, just gushing and gushing.

Of course, your first thought is, oh, my gosh, I’m losing this baby. It’s too early, I’m losing this baby. I screamed. My husband came. He put me into his car and we rushed off to the hospital.

And so that’s not a great way to start a birth experience. You hope that it’s going to be calm. And I had made a birth plan. I had read about all that stuff. And so I had this plan that I’d have this water birth and it’d be really calm. And [laughs] it just didn’t come to pass that way. It was quite stressful.

August (narration):

Renée’s delivery went on for hours and hours. And because she had been on bedrest, she has missed training classes, like Lamaze. The nurses were talking her through it all, but it was still deeply stressful. On top of that, after about three hours of pushing, she was told that was too much.

Renée:

So it went on too long. And finally the doctor said, “We need to cut. We’re going to need to take him surgically.” And I said, “No, no, no. Just let me do it one more time. Just let me do it one more time.” I summoned all my powers, and she said, “Well, wait a second, I’m going to assist you on this.” And she got a vacuum extraction thing going and I just pushed as hard as I possibly could. There was this suction sound and I felt ripping and it was intense. But, he was delivered. He was there and he was out and someone picked him up and put him off to the side. And then immediately though, he was whisked away, because he was not responding. I didn’t know at that moment, but he was being brought to the NICU for his own intensive care.

August (narration):

He wasn’t breathing, and he was blue. Renée didn’t see any of that, though, because she was having a crisis of her own.

Renée:

Shortly after that, I remember lying there and I’m looking at the OB/GYN and they’re not looking at me. They’re looking down at my lady bits. And I saw this pink basin next to the bed. And it was filling up with blood… And there were tons of rags that she just kept sticking on this metal tray. My last conscious thought was, Wow, that’s a lot of blood. I wonder whose blood that is. And then I just was gone.

August (narration):

She’s not sure if she passed out from the pain or from anesthesia. What she does recall is a near-death experience she endured in that hospital room.

Renée:

So after I’m put out, maybe obviously put under anesthesia, where they’re deciding what to do with me and bleeding out, losing all this blood, I had this out of body experience where I was floating over myself. And I kind of hovered up over my body. I kind of felt this conveyor belt kind of sensation, where I was being pulled into a tunnel. And people always talk about NDEs. You’ve heard it, right? They talk about the white light and how wonderful it is. They see all their ancestors and they feel this sense of love. That is not how it played out for me.

I saw dark spirits swirling around me. I saw something that you don’t want to see. The only way I’ve ever been able to make sense of this is like, I was not going to the heaven place. That was not what was happening. I had a really bad experience. And I saw a little edge of hell.

It was very, very scary. There was a chipper sensation, like cutting me at the legs—doot-doot-doot—and it was kind of going up, up, up, up, up, up. And the next thing I knew, I sort of felt like I was reaching out to grab onto the sides of this invisible chipper or whatever that I felt like I was being pulled into on this conveyor belt.

I was filled with two things at the same time. One, this absolute knowing that I was going to die and I was never going to get to be a mother, which I’d wanted to be so much. And the second thing was that something had come into my body, that like a spirit had come into my body, that I had seen this other side and something had actually joined my body. And I came out not alone. Like I brought somebody back with me. An entity. It’s very hard to explain, but the feeling was that something had joined me.

August (narration):

When Renée came out of that, she was told that her son was doing fine. They wheeled him in from the NICU in a little bassinet, and she was able, miraculously, she said, to nurse him.

Renée:

And they got me up walking and I didn’t have dizziness. All of the things they said I wasn’t gonna be able to do I was able to do.

August (narration):

And that was all positive-

Renée:

-but I wanted to talk about this crazy experience that I had had. I wanted to talk to people about like, “Hey, I had this bad experience. I’m super scared right now.”

And, obviously, this is my unique story, but I’ve heard from so many women, in their birth stories, that that’s what they’re told… They’ve had a difficult experience, and told, “Oh but focus on the baby’s here, that’s the miracle, ” or “she’s here,” or “they’re here.” And it’s totally denying the woman’s experience. It’s great that the babies here, but we have feelings, too, that need to be heard and seen and healed, frankly.

There was one of your guests who said this at one point, I can’t remember which one but she said like, if women walked around—I’m badly paraphrasing her—with the wound associated with childbirth, outside of their body people on the street would be like, “Whoa, what happened to you?… That’s a pretty deep gash, you got there!” And because it’s invisible and it’s internal, you can’t see it…

Kimberly Ann Johnson (soft music in the background):

Nobody likes the word recovery. Well, why should I recover? Women give birth all the time? I’m badass. I’m just gonna get back to it. But the fact of the matter is, if we had the wound site, externally that we have internally from where the placenta leaves the uterus, no one would ever think of going outside.. It’s like a dinner plate-size wound site where the placenta detaches from the uterus… You lose a ton of blood. Your progesterone drops 300%, when you birth the placenta. So there’s so many physiological processes. There’s 16 suspensory ligaments that hold up the uterus that become kind of like loose taffy, and they need time to gel back up. But you can’t see any of that. So it’s all mysterious. And it’s all internal. And we don’t think about our organs until they’re bothering us.

Because it’s not an embodied culture, and we were not really used to using our body as our compass and our intuitive radar, we just think, Well, you look pretty good. And even if you don’t, whatever, let’s go to Target.

August (narration):

That was Kimberly Ann Johnson, a sexological bodyworker, birth doula and author of the postpartum guide called, The Fourth Trimester. I interviewed her in July, 2018.

Renée:

That has been such a metaphor for my whole entire last eight years about things that are invisible that need so much more attention and nuance.

August (narration):

Another common challenge is sleep—or, more specifically, how to get enough of it. Most parents struggle with rest, especially when they have a newborn at home. They’re woken up at all hours of the night, and often to try and squeeze sleep in when the baby is napping – and that’s only if their schedules allow.

Renee’s sleep challenges were so much more than that. She described it all as “next level insomnia.”

Renée:

I sort of came home from the hospital a mess. I lost 75% of my blood during the delivery.

Lots of people ask me, “Why didn’t you transfuse?” Well, Derek was really adamant… Around this time, there was a lot of worry around HIV and Hep C, and he was like, “Look, you don’t have to go back to work. Why don’t you just slowly grow your blood back and instead of adding an additional risk? We’ll just do it that way. We’ll get a personal care aid for you and you can just slowly grow it back.”

And it seemed at the time like it was the right thing. And maybe it was, right? There was a physical solution that we were trying to do, but I could not sleep.

August (narration):

There were multiple layers to the insomnia, she said. There’s the usual aspect of parenting a baby, when you’re woken up frequently, or anticipating your baby waking up. She was also nursing, so her breasts would get firm. And, she was dealing with the trauma of her difficult delivery and all that entailed. Sleep often suffers after a traumatic event.

For Renée, there was another layer, too – one she couldn’t have anticipated.

Renée:

I really had this other experience where I would lie down and I just heard voices telling me to do things. And not scary things, not to hurt myself or anything, but I could hear voices, like if someone was talking in another room. It just sounded like muttering. I’d wake up my husband and be like, “Do you hear that?”

August (narration):

Renée compared the experience to Whoopie Goldberg’s character in the movie, “Ghost.”

Renée:

She’s like suddenly really hearing Spirit. And truthfully, that was what was happening but I didn’t have any way to know what that was.

And so not only was I having this very strange experience of hearing other voices, but I was also being told to be quiet: “Don’t tell people that. Don’t talk about that. Just be happy and just keep nursing your baby.”

August (narration):

There is such a pattern in Renee’s experience, throughout all of this, where she gains some kind of awareness or speaks up about a challenge and then gets pushed down. Then she speaks up again and gets pushed down. And for a long time, even well-intentioned people and seemingly smart efforts ended up not being terribly helpful.

Renée:

Because my husband was a doctor, he was just like, “Girl, you got to get to a doctor because there’s something wrong.

August (narration):

She went to see her primary care doctor, who prescribed various antidepressants.

Renée:

We tried Prozac, we tried Zoloft, we tried Celexa, like three different kinds of antidepressants. And while those may work for some people, they wound me up and made me twitch and tick and it was actually quite scary.

They made me kind of manic. If I wasn’t sleeping before, now I really wasn’t sleeping, and I felt very wound up and accelerated. That was the point where my then husband said, “We’ve got to get you an appointment with a psychiatrist.”

August (narration):

So they did. She got a referral and her appointment arrived-

Renée:

-and within 15 minutes with this psychiatrist, I was diagnosed with anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder. All those things sounded really scary.

August (narration):

How could they not sound scary, given that she was given no real explanation – much less, a proper exam? Fifteen minutes. That just blows my mind.

Renée:

From a checklist. Like there were 10 questions. It was ridiculous.

August (narration):

Ideally, being diagnosed with a mental health disorder is a process—a thoughtful and in-depth one that includes lots of conversations, discussion of your past, your family medical history and more. But that was far from the case for Renée.

I had chills – more like quivers – as she spoke about that, and while reading her book…especially knowing where that experience would lead.

So the doctor led her through that quick checklist-

Renée

And he wrote me a prescription for Lamictal, which was for the bipolar. I was also given clonazepam or Klonopin, which was a benzodiazepine.

August (narration):

Renée figured, he’s a doctor so he must know what he’s doing. And regardless, by this point she was feeling quite desperate.

Renée:

My son was born in 1999. At this point, it’s like 2001, I want to say? So years of insomnia kind of wore me down. And when this guy said to me, “I have a tried and true medication that’s going to help you and it’s just a baby dose, and there’s no risks associated with it,” I really wanted to believe him.

August:

And at first, you did have good sleep. I was so happy you had the relief, even knowing where it was going.

Renée:

I remember the first night I took it. Within 10 minutes, I was asleep. And the next day I woke up and it was like out of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”…like I heard the birds chirping [soft chirping] and I didn’t feel uptight. And I just went, Oh, my gosh! I called it a miracle drug. And I took it exactly as prescribed for the next seven years.

August:

And no one told you that it was not supposed to be used for long term.

Renée:

Correct. And in fact, at the time—so this is back in 2004 now, I guess, because by the time I was ramped up to that it was around 2004 where I was taking it daily—I was told it’s completely safe, it’s a baby dose, non-addictive, and that it might actually even help me to lose a little weight. And in our culture, if you can take off a few pounds easily, what woman’s gonna say no to that, you know? It wasn’t a drug that was gonna add weight; I might lose a couple pounds. You know, that’s not a healthy way of thinking either, but this was the allure. And it worked for years, and nobody questioned it.

And to be fair, there is a recent change with the FDA labels. But in 2004, that knowledge was not there. So I just want to be clear, all this information is now forthcoming at this point, but people were not concerned. And in fact, my own husband at the time was like “I see people on 10 times this amount. You’re fine. It’s a baby dose.”

August (narration):

And for those seven years, Renée thought she really was fine.

Renée:

At first, it was great! I slept, I felt actually quite energetic. I was very productive because, the truth be told, August, and you knew me back then when we were bloggers together, I was very productive, because I could stay up as late as I wanted, and then take a medication and within 15 minutes, I was out. And I would get eight hours.

But, over time, I started to have a lot of other issues which nobody attributed to the psychiatric meds at all. So I started to have very frequent urinary tract infections. I had yeast infections. I had a tightness in my throat that wouldn’t go away. I had muscle spasms.

One night I went dancing and I actually thought someone roofied my drink because from out of nowhere, I was like, whoa, I’m super dizzy. And what it was was that I was a little bit late with my medication that night because I was out having fun.

I didn’t recognize it at all at the time, but that was the first sign that I was having that little bit of tolerance, that I’d hit that place that I needed more, you know? I needed more. And that was what the doctors always did. They would just give me a little bit more. So my prescription went up, from what .25 milligrams to .5 to 2.75 to one. And by the end of the seven years, I was up to 2.25 milligrams of Klonopin. So it went up almost 400%.

August (narration):

One day she went to see her doctor to have her prescription refilled as usual and he was not there.

Renée:

There was a note on the door. The note basically said, hey, the doctor has decided to not practice anymore. Go and find a new practitioner from your own primary care person. So I went back to my primary care. I had no idea about this so I said, “Can you just write for me? It’ll be so much easier.” And he said, “Yeah, no. I can’t write for you. This is a controlled substance.” And I went what? You know, no one had ever said, boo. And he said, “I can’t write this for you. You’re going to need an addiction specialist.”

August (narration):

That was the first time she had heard the word ‘addiction’ in connection with the medication she had been taking. Still, Renée wasn’t terribly concerned about any of this. She figured she would just switch doctors and everything would be fine.

Renée:

Yes, I switched doctors. And I’m actually going to name her. So I ended up with Dr. Patricia Halligan. This is like one of those “there but for the grace of God” moments because she actually was here at the time, in Rochester, New York. Now she is sought all over the country, all over the world. But she was like 20 minutes away from me, right here in my town. And she knew how to get people off of these medications.

Now, I have to preface this with something. There doesn’t seem to be any correlation between how long someone’s been on these drugs and the experience they have coming off of them. It seems to be a very individualized experience. Some people could be taking these from 19, 20 years. I don’t know what their genetics are, but they seem to come off them without problems. Some people take them for two weeks and they have problems for years. So it’s sort of a Russian Roulette kind of situation here.

But what she did know was that if you take people off of benzodiazepines too abruptly, you can have seizures. And her goal, or a goal, is to try to do it slow enough so that you don’t further injure your brain and have seizures.

So, that’s one of the things I like to be very clear about because sometimes when people, or even hear this episode, I don’t want people to feel like oh god, well, then I should, I’m just gonna get off of this. You have to take it very slowly. Because even at the end, even if you have some problems like the way I had some very significant problems, the goal is to not make worse problems for yourself.

August (narration):

Renée added that you should never stop a benzodiazepine abruptly ever, ever, ever. And if you do wish to stop, you need help. The same applies to many other substances and medications.

And she tried to do that, to go about stopping safely. And at first, it went pretty well.

Renée:

So I met with my doctor and she said well, like “Let’s set up a schedule,” and so we set about slow – it was a slow medically-supervised taper. It was about 10 months.

Basically I would get a little scale and I was cutting my medication into little bits and pieces and holding the rest and just I was just cutting it into smaller and smaller pieces and weighing them and trying to get the correct amounts.

August (narration):

Klonopin is stronger than valium, and she was dealing with tiny little micrograms.

Renée:

And so there comes a certain point when a drug is that strong, that you can’t cut it small enough anymore. You know, you’re talking about micrograms. So I had to cross over from the Klonopin to the Valium, and then continue to taper down further. So eventually, I got down as far as I could go with cutting the Valium-

August (narration):

But that’s where things got confused. She didn’t realize it at the time, but she was supposed to continue with something called a water titration – where a pill is mixed with water, so you can more precisely measure those increasingly small doses.

Renée:

And I was supposed to go to a compounding pharmacy and have new little tablets or capsules made up where I would have continued all the way down until I got down to 0.00. And that would have been the day. But I didn’t know that information. So I ended up jumping off at what I believe was about…0.125 milligrams of Valium, which doesn’t sound like very much. But remember, I had been taking this stuff for seven years. And I probably needed another six months of tapering.

And it wasn’t even a decision. It was like my doctor went out of town. I couldn’t get a hold of her. There were no further instructions on my little yellow pad of paper. And so I went, I guess I’m done. I think I’m done.

August (narration):

So that was it. She stopped taking the medication. And she and Derek decided to commemorate it with a nice dinner out. [soft jazzy music] She even bought a new dress.

Renée:

You know we were celebrating, because I got off of it. And everything was kind of okay for a few days.

August (narration):

But Klonopin has a half life that’s longer than other drugs – some 30-40 hours, according to the FDA.

Renée:

And so about 10 days after my last dose, I felt this very strange experience. I started to experience a kaleidoscope effect with my vision.

August (narration):

Derek, who’s an ophthalmologist, told her it was an ocular migraine.

Renée:

And I was kind of like, I don’t know... And that went on for a few days. Things just didn’t seem right… I didn’t feel well. It’s a very hard thing to explain. But I felt like the world tilted. Things were not right.

August (narration):

She had headaches, fatigue. Everything felt too bright, too loud.

And things were getting worse.

Renée:

One morning I walked down the stairs and I just looked outside and I said something is not right. And I heard these three clicks in my brain. I’ll never forget it. It’s that sound of a thermostat, like if your thermostat clicks on that sound – that, click-click-click sound.

August (narration):

A moment later, she was down on the ground.

Renée:

And I was having a seizure. I had pulled myself off of the medication too quickly.

I stayed there on the floor all day. And when my husband came home at the end of the day, he saw me on the floor and he escorted me upstairs and I stayed there for several weeks in bed. I was just really debilitated – couldn’t walk, couldn’t talk, blinds down. It was bad.

August (narration):

Renée had no way of reaching her doctor, who was still out of the country. Derek didn’t know what to do. She thinks, in his own way, he was trying to protect her by letting her rest at home.

Meanwhile, she was barely eating. She lost weight. She wasn’t sleeping. She couldn’t even bathe. She said it was similar to back when she first started hearing voices, but “times 1,000.” One of the most excruciating parts was muscle spasms.

Renée:

If you imagine being electrocuted and you’re holding on to like a wire that’s electric heating you and you can’t let go of it. It’s just continuous brain zaps. And imagine that somebody’s also hitting you in the head with a hammer at the same time, while your muscles are cramping up. Your feet are cramping up while your ears are ringing, while your eyes are tearing, because your vision is messed up. Even the sheets hurt your skin. It’s like being in an invisible torture chamber that you just can’t escape.

August:

It’s unfathomable. But you write about it in such a vivid way and speak about it in such a vivid way that we can start to imagine and I think that’s really important. And it’s so sad to me that people, when we are in the most dire straits, we have the hardest time getting help, because our brain isn’t working. It’s just such a horrible Catch 22 that when we are in the deepest of trauma and we need the most help we are on the ground and dying.

Renée:

Yeah. And what is that? That’s like some primitive thing, right, that protecting you so it makes you want to hibernate and not ask. And I was too scared to ask people. I just needed blood to get to my brain and my heart or something. And anything else seemed like a threat. It was a very, very strange thing. I didn’t want anyone to come and see me…Yes. That is a trauma response. A profound trauma response.

August:

Were you thinking on some level that it’s just gonna wear off?

Renée:

Yes! Absolutely. Because I was not an innocent girl. I mean, I may have been brought up like a little good Jewish girl. But I had experimented with some drugs in college. I had tried psilocybin mushrooms and some other things. And they had come down off of them. It was like, oh, I’m tired the next day or something. And I had that trippy feeling, and this is what it feels like. It feels like you’re stuck in a bad trip. And so I just kept thinking, well, it’s got to end. It’s got to end like every other bad trip ends, you know? The experience ends. How long could it last?

The good thing is it did eventually end but the horror is years. I’m eight years off now. Eight years of that, where it was like being in a bad trip while you’re in a torture chamber while you’re being electrocuted. It’s just really difficult.

August:

You did end up meeting a woman who was very helpful to you. And she’s almost like this fairy angel or something who comes into your life.

Renée:

Yeah, like my Glenda. Those are the things like, “look for the helpers,” right? This is truly evidence that it was not my day to die.

I had gone to get a massage and it was awful. I couldn’t have anyone touch me. I was too sensitive. And I left the massage place like after 15 minutes of trying…I couldn’t take it. And I went outside and I basically decided that I was going to kill myself. Like, this is it. I’m going to jump off this building. And I was crying. And I was a little sad for my son. But also, like you said, our brains aren’t working. So I was kind of thinking to myself, what good am I to anybody? I’m no good to anybody at all like this. I can’t do anything, I can’t work, I can’t talk. I can’t make it to the bathroom. I’m such a burden. Everyone will be better off. And I truly believed it.

I was also in so much physical, emotional and spiritual pain. I was so disconnected from myself. So I was gonna jump and I was crying and this woman approached me and just crouched down and she said, “Hi. Are you okay?” I just said, “Nope! No. I am not okay. I am actually in withdrawal after coming off of a very powerful anti-anxiety medication, and I can’t do this. I can’t do it. And I’m going to jump off of that building right there.” And she kind of looked at me and she cocked her head and she said, “Hmm. You wanna come home with me?”

I didn’t know her. I didn’t even know her name. I didn’t know where she lived. But what does it matter? Because I was gonna jump, right? So if she was gonna kill me, awesome. Like, make it snappy sister.

August (narration):

So Renee followed the woman, “like a stray puppy dog,” stepped into her car and they started driving. Then, she learned the woman’s name.

Renée:

We were in the car talking. And she’s like, “I guess if you’re coming home with me, I should probably know your name.” And I said, “My name is Renée.” And she was like [vocal car sound] pulls over the car. And she’s like, “Are you kidding me?” And I said, “No. Why?” And she said, “My name is Renée, too.” Wow. It felt like a really neat experience for both of us, very divine and like it felt like divine intervention.

August (narration):

And that was only the beginning. Renée lived with the woman off and on for about six months, teaching her about nutrition, meditation and the importance of good sleep hygiene.

Renée:

She just blew open my world to a whole other kind of knowing because I came from a medical, you know? This family that I had married into was a medical model. And she was all about something else, which was very self-empowered and holistic, and about treating the whole person rather than symptoms.

August (narration):

Little did Renée know that the woman had been wanting to open a healing center for years.

Renée:

She had been bringing people home to their house for years. I wasn’t the first stray she brought home. [laughs] And her kids had that response to me. They’re like, “You’re not the first one. Don’t worry about it.” I would be lying around on the floor writhing in pain and they’d step over me and go make a peanut butter sandwich or something. They were all wonderful.

August (narration):

Over time, the woman continued to provide Renée with all sorts of free, holistic therapies.

Renée:

She got me bodywork. She got me therapeutic massage. I had acupuncture. Like all kinds of things that I’d never heard of or had any access to. These things started to break it up for me. It was like my world was blown open to all different kinds of non-ingestible… It wasn’t the supplements, it was outside-the-body kinds of things. And I started to feel better. I started to feel better.

August:

Do you remember that moment? Or one of the moments when you felt like ah, wow, like the leaf has turned?

Renée:

Yeah, I actually do.

August (narration):

It was during an hour of cranial sacral massage, a therapy that uses light touch, focused on the head and spinal column to move fluids around your nervous system and relieve tension. It’s also believed to help move trauma that’s stuck in your body.

Renée:

I had this session and I sat up and I looked around and I was like, Oh my God, I feel okay. I feel okay! I was kind of scared to even say it… And I remember I went to the grocery store. I actually ran into a friend… We had a conversation. It wasn’t normal. It was weird. But I was better than I had been for years at that point.

August (narration):

It was a big moment for her, because she thought, if she could experience that for one hour, she could experience it for two hours.

Renée:

People in the recovery community talk about windows and waves. We talk about [how] it’s not a linear healing, this thing. So it’s not like when you cut your hand and you just notice that, it scabs and eventually falls off. It’s not like that. You have some days that are better and then days that are worse. That was not my experience. I was just awful the whole way until this one day where I had this one good hour. It was heaven sent, because I really needed that hour to feel like, Okay. For whatever reason, that happened. And so I know that it can happen again.

August:

It sounds like you had hope.

Renée:

You know what? That is it. I had hope. I had hope restored. And I guess on some level I always had hope because otherwise I would have jumped.

[hopeful, acoustic music]

August (narration):

All of that work ended up healing trauma that Renée had been carrying for years, beyond her dependence on benzos. She was able to make some peace with those experiences and settle her nervous system, she said, so that her body knows she’s safe. That those painful things aren’t happening now.

As she was healing and spending a lot of time in bed, she also started painting—beautiful creations. Given her brain injury, she couldn’t spend time reading. She said that painting filled that space. And when she posted photos of her paintings online – like “here’s what I did today” – people started asking to buy them. Renee was floored by this, and it led to some of the advocacy she continues to do today.

Renée:

I had been a teacher for 20 years. I wasn’t painting, you know? This was crazy. And so, over time, I started to ask other people, is anyone else going through anything similar? Thinking I’d find other people with benzo issues. And I was so amazed that people sent me pictures of themselves and asked me if I would paint like an abstract portrait of them, and share their story with me. And it just became part of my artistic practice. And it was a way to connect with people when I really couldn’t connect with people in person yet. And it really was quite healing.

And what I realized then is, we might feel like we’re alone, but wow, we are never alone. Anything that anyone is going through, you are not alone.

August (narration):

And like most healing work, it’s all impacted Renée’s sexual self, too.

Renée:

I feel like I’ve had so much healing in that area, too. I have met some people who have helped me in that area to show me that they appreciated my passion and my libido and they didn’t think that it was crazy or bad or too much. So that part was very helpful and healing.

That being said, I haven’t quite been able to put it all together or find the right person yet to be in a relationship with. But that’s okay, because I actually believe that it will come when it’s the right time, and that it hadn’t been the right time. But I definitely feel like the next relationship that I get into I will be able to remain true to myself without losing myself in a relationship, the way that I did, without making myself small the way that I did.

I’m so firm in my nos now that I know when I can say yes and when I can say no. I feel like that’s a really big part of this journey, for everybody, but women especially. We are not socialized to say, no. We’re not socialized to say, “I can’t do this, I’m sorry,” or “I’m going to need extra time…” Whatever we need to say. And I’m so in that power now. It’s never going away. So I do feel like the most healthy relationship is headed my way.

August (narration):

As for her overall journey, and her relationship with herself, Renée has recently started using the word – past-tense – healed. She told me she is completely clear on her purpose in this world.

Renée:

So I’m an artist. I am here to write, I’m here to teach. I was always a teacher, I’m teaching in a different way now. I am here to make the world beautiful. I am here to help people discover this side of themselves that everyone can be a maker and a creator. I’m here to teach people that they don’t have to be perfect. The other thing that I do is I actually offer emotional support to people who are going through this injury with the legal prescriptions psychiatric medications, people who are trying to come off of their medications. Not everybody is in that place, but for people who are, I offer emotional support to them.

And I obviously know that there are other challenges that are going to come into my life, you know? But I feel so much more capable having gone through this experience. I feel, I’m gonna just say it. I think I’m allowed to swear on here. I feel unf*ck-with-able. I really do. I feel like I have the skills to make it through the rest of my life, to ask for what I need when I need it. And to not stop searching, even if the first person says no. And I’m going to find it because there are people who are going to be able to help me no matter what challenge I have.

I didn’t have that before, I was always looking for somebody to fix the broken me. And I realized that I’m here this time to express myself fully, be my most authentic. We all are, by the way. It’s not just me. We’re all here for that. But doesn’t it sound easy when you say it? Doesn’t it sound like, “I’m my most authentic!” When I was on the drugs, I would have said to you that I’m being my most authentic self. That’s the creepiest part. I really thought that I was. But off of them now, I’m like, oh my gosh. I know I’m a force.

[acoustic chord riff]

August (narration):

There is, of course, so much more to Renée Schuls-Jacobson’s story. For a powerful deep dive, find her book. Psychiatrized: Waking up after a Decade of Bad Medicine on Amazon. It’s available in paperback, ebook and audiobook forms.

You can also hear a few more snippets from our interview, including about a spiritual experience she found especially healing and her tips for starting to live more authentically, on Patreon. If you’d like to reach out to Renée or explore her artwork, you can do so through her website.

I’ve got a little song which I always say: I’m always making something I’m an artist to the core rasjacobson dot store.

August (narration):

That’s rasjacobson.store.

If you’re enjoying Girl Boner Radio, I’d love to hear from you by way of a review on Apple Podcasts or the iTunes Store.

And if you give this episode’s sponsor, Zencastr, a try, using this special discount link (30% off for 3 months, after a free trial), I want to hear about it.

Thanks so much for listening.

[outro music that makes you wanna dance…]

Leave a Reply